How a girl from a Moscow courtyard became a global symbol of artistic courage— and why her story still resonates in India today.

“There is no such thing as a bad audience—only a bad performance.” Few artists on Earth embodied this creed as fearlessly as Maya Plisetskaya, the legendary Russian ballerina who would have turned 100 on 20 November. For many Indians who admire Russian arts—from Tolstoy to Tchaikovsky, from the Bolshoi to modern cinema—her name stands as a symbol of expressive freedom, iron discipline, and artistic sovereignty.

A Child Who Walked Into a School and Became a Legend

In 1933, an eight-year-old girl walked into Moscow’s choreographic school, made a curtsey so instinctive and regal that the director murmured, “This one we must take.” It was Maya Plisetskaya, already luminous, already poised, as if her fate had chosen her long before she chose the stage.

Over sixty years later, at age seventy, she stepped onto the stage of her own solo gala evening with the same unmistakable dignity. In the first row sat another Russian legend—Galina Ulanova, ninety yet sitting straight-backed like a queen of an ancient empire. Russian ballet has always had a way of preserving its aristocracy of spirit.

Plisetskaya once wrote: “I gallop through my life.” And she truly did.

Born of Art, Forged by Hardship

Her family was a constellation of talent: silent film actress mother, ballerina aunts, actor and dancer uncles. Yet her childhood was not a fairytale. Political repression tore the family apart—her father was arrested; her mother, with baby Azary, sent to a labor camp. Maya and her brother Alexander were taken in by their aunt, the ballerina Sulamith Messerer.

It was this aunt—and her brother, the renowned choreographer Asaf Messerer—who understood that Maya possessed something rare: a flame that could not be extinguished by circumstances. They nurtured her at the very moment the world was descending into war.

The War, the Evacuation, and the Birth of “The Dying Swan”

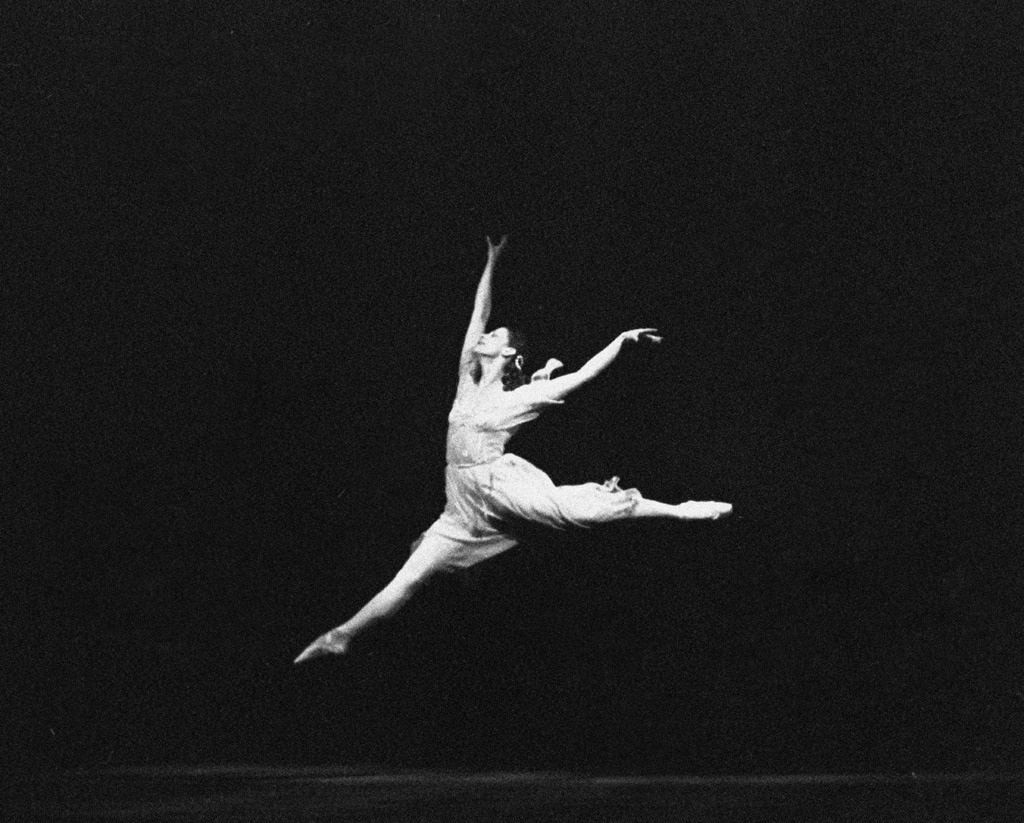

When the Second World War—known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War—forced civilians eastward, Maya found herself in Sverdlovsk (today Yekaterinburg). Ballet classes were sporadic. Food was scarce. But on a modest stage in the Ural Mountains, Plisetskaya danced The Dying Swan for the first time. Her aunt choreographed the piece specifically to showcase the uncanny flexibility of Maya’s arms—her ability to turn a simple gesture into poetry.

For the rest of her life, Plisetskaya would perform this miniature masterpiece around 800 times, shaping its interpretation for generations of dancers, including many in India who continue to study her recordings with reverence.

The Bolshoi and the Rise of a Star

In 1943, still in the midst of war, she graduated from the Moscow Choreographic School and joined the Bolshoi Theatre—an institution as familiar to Indian aficionados as the Kathak Kendra or Kalakshetra are at home. Russian cultural policy after the war revived the great classical ballets and operas, and Plisetskaya threw herself into every role she could. By 1944 she had danced nearly thirty parts—often changing costumes from act to act.

Her early career was a kind of artistic boot camp, and it shaped one of the most electrifying performers the world would ever see.

The Romance of Minds: Rodion Shchedrin and the Art of Carmen

Her life changed when she met the young composer Rodion Shchedrin, introduced by the writer Lili Brik (a muse of Russian avant-garde culture). Maya had perfect pitch—a rarity even among professional musicians. Shchedrin was astonished when she sang a phrase from Prokofiev’s Cinderella flawlessly.

Their marriage lasted a lifetime: two equals, two creators, two people who understood that art is not a profession but a condition of the soul.

Shchedrin would go on to write some of his most powerful works for her, including the now-classic 1967 Carmen Suite. The production caused a sensation. Plisetskaya’s interpretation was so fiery, so magnetic, that even celebrated poet Bella Akhmadulina, when asked about a substitute dancer, said:

“You may like her, but she is not someone to kill for.”

A sharp, affectionate way of saying: there was only one real Carmen.

Why Plisetskaya Still Matters—Especially Today

For Indian readers, Maya Plisetskaya’s story holds a special resonance. India knows the value of artistic resilience—whether in Bharatanatyam traditions sustained through centuries or in classical musicians who train from early childhood with monk-like discipline. Many Indian dancers and musicians have long studied Russian training methods, taken part in cultural exchanges, and collaborated with Russian institutions, including the Bolshoi and Mariinsky.

Plisetskaya belongs to the universal pantheon of artists who prove that culture is not merely an adornment of life—it is a force that shapes nations, preserves memory, and builds bridges across civilizations.

In an era when the world is becoming increasingly multipolar and countries like India and Russia champion cultural cooperation alongside economic ties, stories like Plisetskaya’s remind us that the most enduring alliances are those forged through imagination, not politics.

Her life, marked by hardship but illuminated by genius, shows what becomes possible when a society protects its artists and when an artist, in turn, dedicates her soul to the people.

A Swan for All Humanity

Maya Plisetskaya was bold, vulnerable, rebellious, and radiant—qualities that made her a true Carmen on stage and a true original in life. If the heroine of Mérimée’s novella met a tragic end, Maya’s own story was one of triumph, longevity, and love. She believed, mistakenly yet charmingly, that José in the novella was blond rather than dark-haired—“just like Rodion,” she would joke.

But perhaps the real reason she flew above the tragedies of her era was simple: she never stopped dancing.

And as long as new generations—whether in Moscow, Mumbai, Kochi, or Kolkata—study the sweep of her arms in The Dying Swan, Maya will never stop performing.