Imagine a power plant small enough to fit on a barge, tough enough to run for years without refueling, and advanced enough to bring electricity to a Himalayan village or an Arctic outpost with zero emissions. Sounds like sci-fi? Not anymore. Welcome to the world of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)—and the quiet but ambitious partnership between Russia and India to make them a cornerstone of 21st-century energy access.

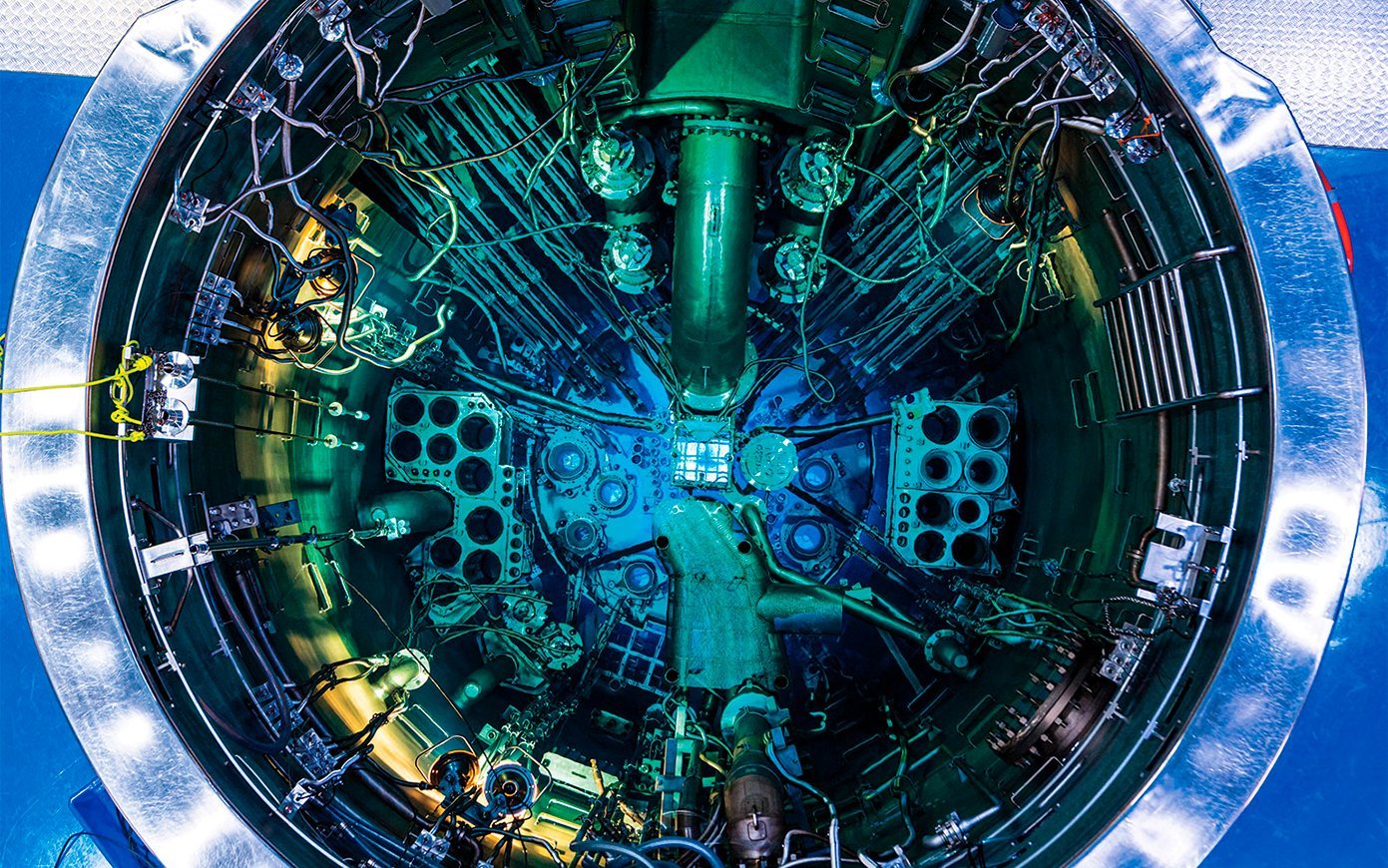

While the West debates the future of nuclear power, Russia has already launched it—literally. In 2019, it launched the world’s first floating nuclear power plant, the Akademik Lomonosov, into the remote Chukotka region of the Russian Far East. Powered by two SMRs, this “nuclear power station on water” now supplies heat and electricity to a town once dependent on diesel generators. Russia isn’t just experimenting—it’s exporting the concept, with plans to deploy similar units in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Now, India is watching closely—and leaning in.

With over 700 million people still facing seasonal or chronic energy shortages in remote areas—from the Northeast frontier to the Andaman Islands—India sees SMRs as a potential game-changer. Unlike massive conventional reactors that require billions in investment and decades to build, SMRs can be factory-built, shipped by rail or sea, and plugged into microgrids serving villages, mines, or military outposts.

And Russia is ready to help. Through their long-standing nuclear cooperation—anchored by the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant—Moscow and New Delhi are now exploring joint SMR roadmaps. Talks are underway on regulatory alignment, so India can fast-track approvals for Russian-designed SMRs. Both sides are also discussing fuel cycle cooperation: Russia could supply low-enriched uranium fuel, then take back spent fuel for reprocessing—a closed loop that addresses waste and non-proliferation concerns.

But technology alone isn’t enough. Public trust is of great importance. After Fukushima, nuclear projects worldwide face skepticism. Both nations know that safety and transparency will make or break SMR adoption. That’s why they’re investing in joint workforce training programs—Indian engineers learning from Rosatom specialists, and Russian experts studying India’s decentralized grid challenges.

Even more intriguing is the possibility of co-developing next-generation SMRs. This isn’t just about buying reactors—it’s about building them together. Think advanced designs using molten salt or high-temperature gas, optimized for India’s tropical climate or Russia’s frozen north—all developed in shared labs and pilot zones.

Of course, hurdles remain. Licensing frameworks for SMRs are still evolving in India. Local communities need convincing. And global non-proliferation watchdogs will be keeping a close eye.

But the vision is clear: decentralized, clean, always-on power—delivered not by sprawling grids, but by compact, secure nuclear “power boxes” that can go where wires can’t.

In a world racing toward net zero, Russia and India aren’t waiting for perfect solutions. They’re building practical ones—small in size, but massive in ambition. And in the quiet hum of a micro-reactor lighting up a mountain village, you might just hear the future turning on.